Bromeliads, the Bromeliaceae family, are among the most fascinating plants of the neotropical fauna. Most of them grow too large for a 5l hermetosphere. A few however do not only fit in size but also seem to find favorable conditions for living in hermetospheres.

Initially, the Bromeliaceae family was divided into three subfamilies based on morphological characteristics: Tillandsioideae, Bromelioideae and Pitcairnioideae. Based on more recent studies of compared DNA sequences that allow assumptions of phylogenetic relationships between taxa, eight sub-families are proposed [Gvinish e.a. 2014].

The interesting feature are the adaptions to water shortage that happened within the development of the Bromeliads. This may seem strange at first glance for tropical plants, but it allowed them to colonize habitats other than the soil, where roots can usually extend deep enough to find water and nutrients. In other words, these adaptions made an epiphytic way of living possible. Among the adaptions best understood today are:

- Water storage tanks formed by the leaf rosette of the plants; these tanks often contain entire micro-ecosystems and offer a habitat to algae, insect larvae and frogs a.o. [for a nice overview see Corbara e.a. 2019];

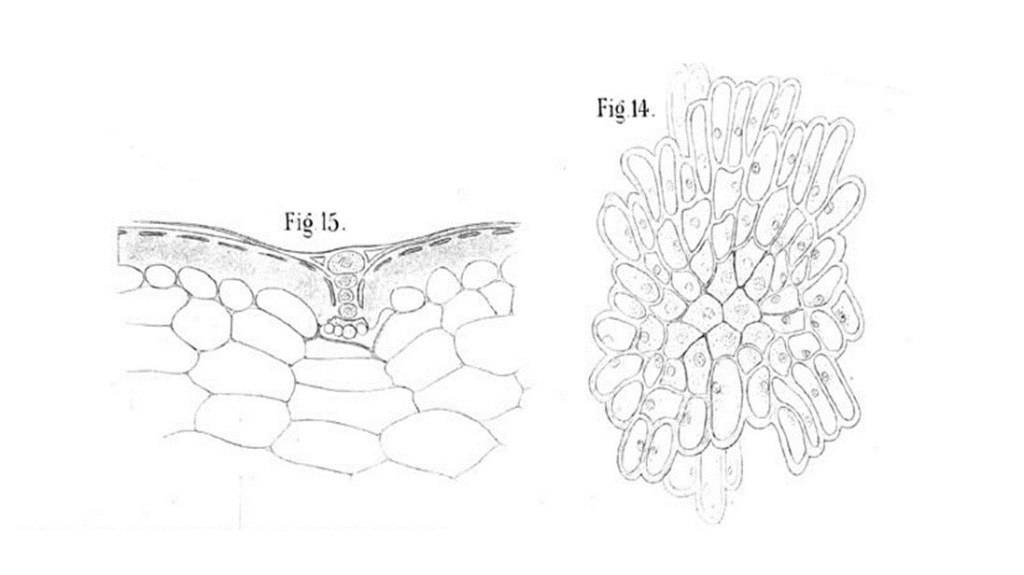

- Trichomes, microscopic, shield-shaped (peltate) structures on the leaf surface able to take up water and nutrients; these structures have been nicely described and illustrated in 1888 by Andreas Franz Wilhelm Schimper in his standard work about America’s epiphytic vegetation [Schimper 1888, see figure below];

- CAM, a photosynthetic pathway alternative to the more common C3 pahway that allows to keep leaf openings (stomata) closed during the day and thus minimizes water loss through evaporation.

Although these adaptions favor epiphytic life, they can also be found in terrestrial forms that live in habitats where water can be scarce.

Today, Bromeliads cover the entire range between purely terrestrial forms without any of the adaptions described and water uptake through roots alone (e.g. Lindmania, Connellia) and purely epiphytic forms that have no roots whatsoever, take up water only by trichomes and rely mainly on CAM photosynthesis (e.g. Tillandsia). Phylogenetic studies reveal that epiphytic forms developed from older, terrestrial forms in early Miocene (see figure below).

Neoregelia lilliputiana, living in one of my jars inspired by the flora of Brazil SE since May 2021, lies between these two extremes. It lives epiphytic in its natural habitat; it develops roots that serve for anchoring in the substrate as well as (assumably) for water and nutrient uptake. Its leaves form a small water tank, and its leaf bases develop trichomes. Finally, the plant can assimilate carbon by CAM photosynthesis. The problem is that in a hermetosphere regular watering of the tank is not an option. So far, humidity in the substrate and condensation from the air seem to be enough to keep the plant happy.

One response to “Neoregelia”

[…] leaf surface, since their roots, if present at all, serve only to anchor the plant (see an earlier post). In a hermetosphere, such a plant is best placed where condensation regularly drips from the lid […]

LikeLike