In viviparous plants, the embryo grows sufficiently to emerge visibly from within the seed tissues before dispersal (Farnsworth 2000). The number of plant species for which vivipary belongs to the usual form of reproduction in their natural habitats is small. Among seed plants, vivipary is well represented and studied in e.g. cacti (Cota-Sánchez 2022) and mangroves (Tomlinson 2016). However, in some plant species where this form of reproduction is unusual, vivipary can occur under special circumstances. I was able to observe this phenomenon within a short period of time in my hermetospheres on two species of the Gesneriaceae family. Find out here about the two plants, the special circumstances of their vivipary and what this has to do with seed dormancy.

Sinningia pusilla is a tuberous miniature Gesneriad native to the Atlantic forest of the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Although pollination of the flowers by butterflies is assumed in nature (Chautems e.a. 2021: 114), self-pollination is also common, at least in cultivation. The three pictures below show what happened in my hermetosphere. My seed-grown S. pusilla produced readily flowers and mature seed pods. The seed capsules have broken open, and, on very close inspection, you can see the ripe seeds inside the capsule. In some seed capsules, the seeds did not fall out but began to germinate inside the capsule. Some seed capsules were also colonised by fungal mycelium, as often happens in the hermetosphere with dead plant tissue.

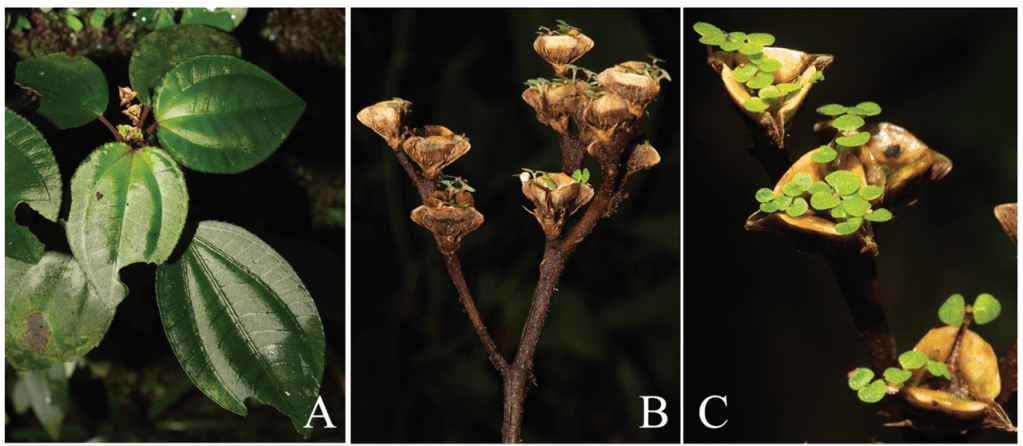

Gesneria cuneifolia is endemic to the island of Puerto Rico and is pollinated by hummingbirds in its natural habitat. It has long been known that the plant is capable of autonomous self-pollination. This is what must have happened to the two flowers that emerged in the hermetosphere in January 2025, as they have formed ripe seed capsules. In nature, “the apex of the capsule splits or withers to form a round opening and exposes seeds, which may be ejected by rain or waterfall splash” (Skog 1976:22). It is assumed that the seeds are dispersed by ants and other invertebrates (Skog 1976:32). In the hermetosphere however, the seeds germinated inside the capsule (see the three pictures below).

Vivipary as defined above is rare in flowering plants in general and in the Gesneriaceae family as well. A literature review by Farnsworth (2000: 109ff.) lists 65 species for which viviparous seeds are documented with a germination study. None of these belog to the Gesneriaceae family. On the other hand, Madison (1977: 10) mentions that vivipary is common in epiphytic, fleshy-fruited Gesneriaceae, but fails to cite a source. S. pusilla and G. cuneifolia are neither epiphytes nor do they have fleshy fruits. So how can the observation of their viviparous seed in the hermetosphere be explained? At this point, it is hepful to understand the concept of seed dormancy.

Seed dormancy means that mechanisms are in place that prevent seeds from germinating as soon as they are mature, even if environmental conditions at the time are favourable. Seed dormancy prevents germination from occurring at a time of the year when the environment does not remain favourable long enough for seedlings to become established and survive (Baskin and Baskin 2014: 5). Seeds of flowering plants growing in arctic, temperate and subtropical zones are predominantly dormant. This seems reasonable, as these zones typically experience periods during the year that are unfavourable for germination and growth because they are dry or cold. What about tropical habitats?

In a study of 5,250 species of flowering plants distributed across all habitats in all zones worldwide, the tropical rainforest was the only habitat with significantly more non-dormant than dormant seeds (Baskin and Baskin 2003: 529f.). However, seed germination of herbaceous species growing in the tropical rainforest has not been studied in very many species. Baskin and Baskin (2014: 445) list 30 terrestrial species of which 57% have non-dormant seeds (one belonging to Gesneriaceae), and 40 epiphytic species all of which have non-dormant seeds (one belonging to Gesneriaceae).

Dormancy usually prevents seeds from viviparous germination. Non-dormant seed however can, under special circumstances, germinate while still in the seed pod in plants that are not known for vivipary. The dominant factor for this unusual behaviour seems to be humidity. Examples for unusual vivipary observed in tropical plants and potentially induced by excess humidity include Jatropha curcas (Euphorbiaceae, Deore and Johnson 2008), Hedychium elatum (Zingiberaceae, Bhadra e.a. 2013).

Bacci e.a. (2021) report six herbaceous, neotropical species of Melastomataceae for which cases of vivipary were identified in individuals in the field. After examining the available herbarium specimens of the species in question, they concluded that viviparous germination is a rare occurrence in these species. They assume that “vivipary may be a consequence of an inefficient dispersal syndrome in which the seeds that are not removed from the fruit by raindrops are still in an appropriately moist environment and can then germinate. Whether these seedlings can then establish and propagate themselves is still to be tested.” (Bacci 2021: 81) One of the documented species is Bertolonia mosenii (see figure below).

view of seedlings inside the capsules of B. mosenii.” (Bacci e.a. 2021: 80; reproduced with permission of The University of Chicago Press, all rights reserved).

Sinningia, like other neotropical Gesneriads, have dry capsular fruits, “ovoid, rostrate with an upturned apex, the two valves opening only slightly, and only splitting the superior portion of the ovary; the insides of the valves with a row of stiff trichomes, releasing the seeds like a salt shaker” (The Gesneriad Society 2025). It is obvious that the release and dispersal of these seeds is facilitated by wind and other movements that are completely absent in the hermetosphere. This makes the seed dispersal in the hermetosphere truly inefficient. Together with the high humidity in the closed container, the observed vivipary seems to be a rather likely scenario based on what we know now. What is more, under the same circumstances, there are probably numerous other species without seed dormancy in which this phenomenon could be observed.