Iridescence is the name of shimmering blue metallic colors of certain plants that appear to change as the angle of view changes. You can find out below how it is produced in Selaginella erythropus, why it cannot be seen with the bare eye and how unusual this is in the plant kingdom. Before that, it is about where the plant is native and how it does in a closed terrarium.

Selaginella erythropus is a creeping or ascendant spikemoss with simple, scale‐like leaves called microphylls on branching stems from which also roots arise. It is prized by plant lovers for its red colouring, from which it gets its name (Greek erythrós = red). The plant is found in forest understories of the neotropics, in deep shade, up to altitudes of 2,000 metres above sea level (GBIF 2025, Vega-Betancur e.a. 2023).

S. erythropus is described and illustrated as green on the upper side (adaxial) of the shoot and reddish on the underside (abaxial) (e.g. Sheue e.a. 2007: fig. 1). However, the variation in colouration appears to be quite large in nature (cf. iNaturalist_2025c). It has been described for various Selaginella species that at higher light intensities, the green colouration ‘bleaches out’ and red pigments are formed instead (Goodwin 1980: 204). I therefore attribute the reddish colouring on both sides of the plants in my containers (see the picture above) to the light conditions.

The three images below show a time series from month 1 to month 7 from the start of the development of the plants in a glass, with S. erythropus in the foreground on the left. It can be seen that S. erythropus grew less in the second half (between months 4 and 7) than in the first half (between months 1 and 4). The colour change from green to red on the upper side of the shoots is also clearly visible. In the meantime, I have changed the location of the container and am allowing slightly less light in. Now I am eager to see whether the new shoots will retain their green colour.

The picture below of two new shoots growing close to the glass wall of the container shows distinguishing features of S. erythropus (Valdespino 1993: 9f.), among them the red rhizome and the dark red stem.

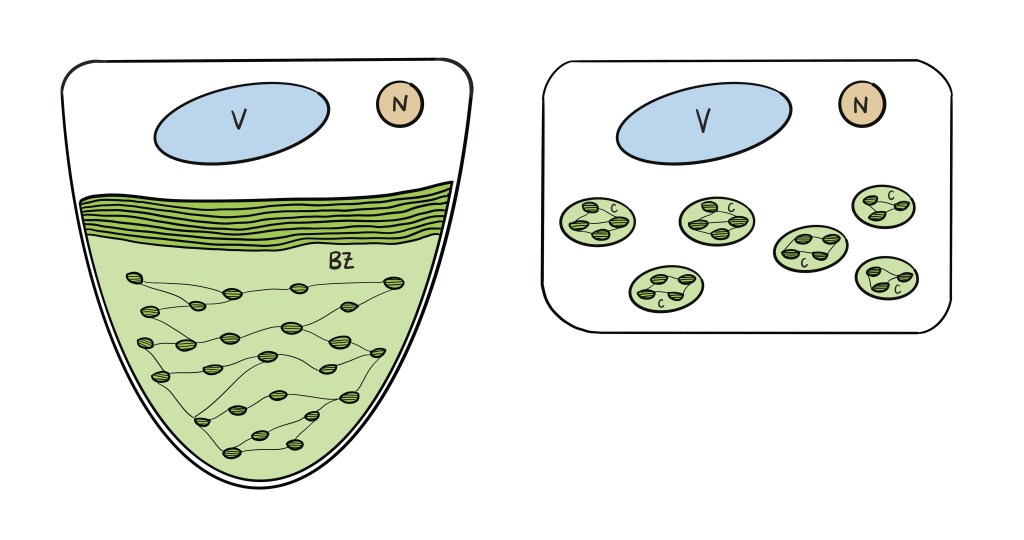

S. erythropus has gained prominence in plant science since 2007 for a previously unknown type of cell. To understand what makes it so special, one must imagine what green plant cells typically look like when viewed under a microscope. You will then notice that the green colour is not evenly distributed, but occurs within the cell in roundish-oval structures called chloroplasts. There are several of these, and they look very similar, regardless of whether you are looking at algae, mosses, ferns or flowering plants under the microscope. Inside chloroplasts, there are stacks of membranes that look like dark granules under the microscope. These membranes contain the green pigment chlorophyll, which is essential for photosynthesis. So much for the normal case.

It was already known that various plants adapted to low light intensities had chloroplasts that differed from the norm. However, when members of an international research group prepared leaves of Selaginella erythropus and examined them under a microscope (Sheue e.a. 2007), they were still surprised. The cells of the outermost layer showed a completely unusual structure. Instead of several small chloroplasts, they found a single, comparatively gigantic chloroplast. The typical membrane granules were only visible in the lower part; the upper part of the giant chloroplast consisted of a single, continuous stack of parallel, layered membranes. These two clearly distinguishable zones gave the newly observed phenomenon its name. The researchers called it ‘bizonoplast’.

This raised many new questions: Would similarly unusual chloroplasts also be found in other Selaginella species? Was there a connection between the newly discovered structure and the iridescence observed in some shade-adapted Selaginella species? What function did the bizonoplasts fulfil in the photosynthesis of S. erythropus? Could genes responsible for the deviating structure be found? Answers to some of these questions have since been found:

- It has been shown (Sheue e.a. 2015) that bizonoplasts in S. erythropus are formed during the transition from young, prostrate shoots to older, erect shoots. However, this only occurs under conditions of low light intensity (ca. 20–30 µmol·m−2·s−1 at midday i.e. about1–1.5% of full sunlight). Plants grown in high light (ca. 450–500µmol·m−2·s−1 at midday i.e. 22.5–25% of full sunlight) did not develop bizonoplasts. Instead, two to four normal-looking chloroplasts were found. It was concluded that the bizonoplast was an adaptation for low light conditions.

- Using various microscopic techniques, Masters et al. (2018) discovered that the membrane stacks in the upper zone of the bizonoplasts cause a structural blue colouration (iridescence) that is not visible to the human eye. They show that Selaginella bizonoplasts present an analogous structure to so-called iridoplasts previously reported for deep-shade adapted Begonia species, where the blue colour is the result of the highly periodic membrane arrangements forming a multilayer photonic structure. However, unlike Begonia species that produce iridoplasts, Selaginella erythropus was not previously described as iridescent. Therefore the possibility of widespread but unobserved and uncharacterized photonic structures in plants is raised.

- Liu e.a. (2020) examined 76 Selaginella species across the genus’ phylogeny and found bizonoplasts smilar to those of S. erythropus in 11 species, all known as deep-shade species (<2.1% full sunlight). Another 33 species showed epidermis cells with various forms of single chloroplasts (monoplastidy) but lacking the distinct division into two zones. All species that are ancient in terms of evolutionary history (basal in the phylogenetic tree) exhibited cells with numerous chloroplasts, as is typical for all vascular plants. From this, they conclude that bizonoplasts are a later differentiation within the genus Selaginella.

- Huang e.a. (2021), in search for the genes responsible for the formation of bizonoplasts, determined the sequence of the entire bizonoplast DNA and found a total of 102 genes. Comparison of the sequence with other Selaginella species also showed that two species closely related to S. erythropus, S. moellendorffii and S. doederleinii, do not form bizonoplasts.

A lot more research is needed, howevewr, to fully understand Selaginella bizonoplasts. How exactly they enhance photosynthectic efficiency in deep-shade conditions – as is proposed – is still unknown. Even more, the increased reflectance in the blue region of the spectrum around 450 nm in the presence of the photonic multilayer structure measured by Masters e.a. (2018) appears counterintuitive: A deep-shade plant, presumably adapted to harvesting as much light as possible, should in theory want to limit the reflection of useful wavelengths of light (i.e. those absorbed by the photosynthetic pigments). Will plant science soon solve these mysteries? I will keep an eye on the progress.