Wax plants (genus Hoya) are popular houseplants. At least this species from southern India also thrives in the hermetosphere. This is the impression I got from the first year of my journey with Hoya kanyakumariana.

The genus Hoya comprises over 300 species of mostly climbing and epiphytic plants. They are distributed from the Himalayas to Australia. The center of diversity is in the perhumid tropical lowlands of the Philippines and in a large area called the Indo-Australian Archipelago, comprising more than 20,000 continental and oceanic islands, and forming a natural corridor for faunistic and floristic exchanges between the continents of Eurasia and Australia (Wanntorp e.a. 2014: 89). At the time of publication of H. kanyakumariana, the genus Hoya belonged to the Asclepiadaceae family. With APG III, the third version of a modern, largely molecular-based system of plant taxonomy published in 2009, the genus was assigned to the Apocynaceae family.

Although most Hoya species are found in tropical climates, many of them have succulent characteristics: thickened leaf blades that can store water, multiple layers of epidermal cells and thickened cuticles for evaporation protection (Hadsall and Rayos 2022). What seems paradoxical at first glance can be explained by the epiphytic way of life without direct access to soil moisture.

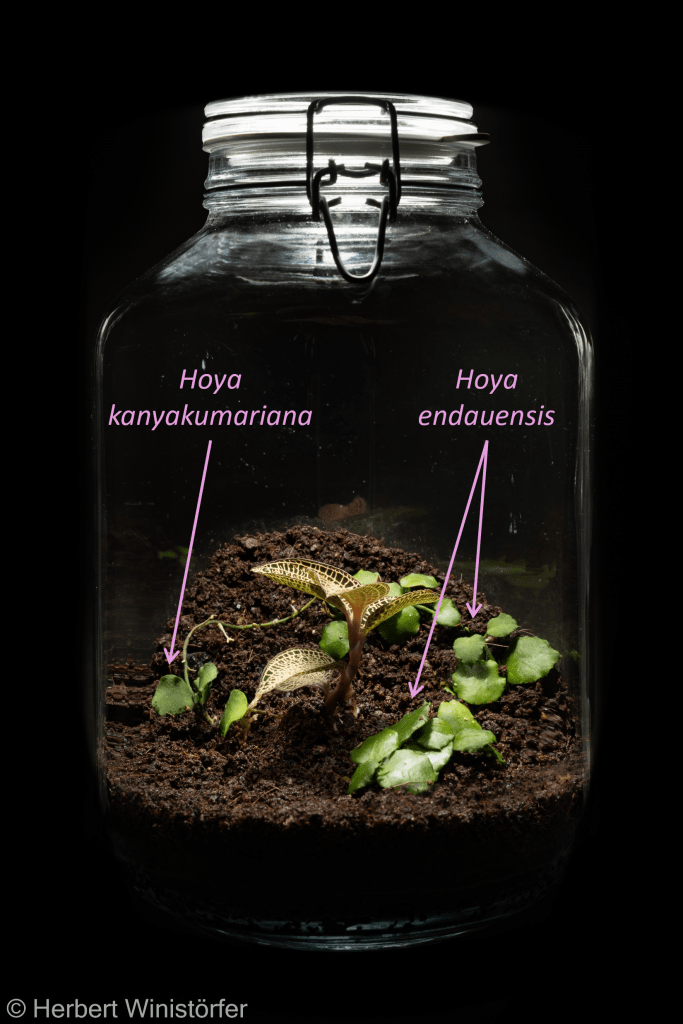

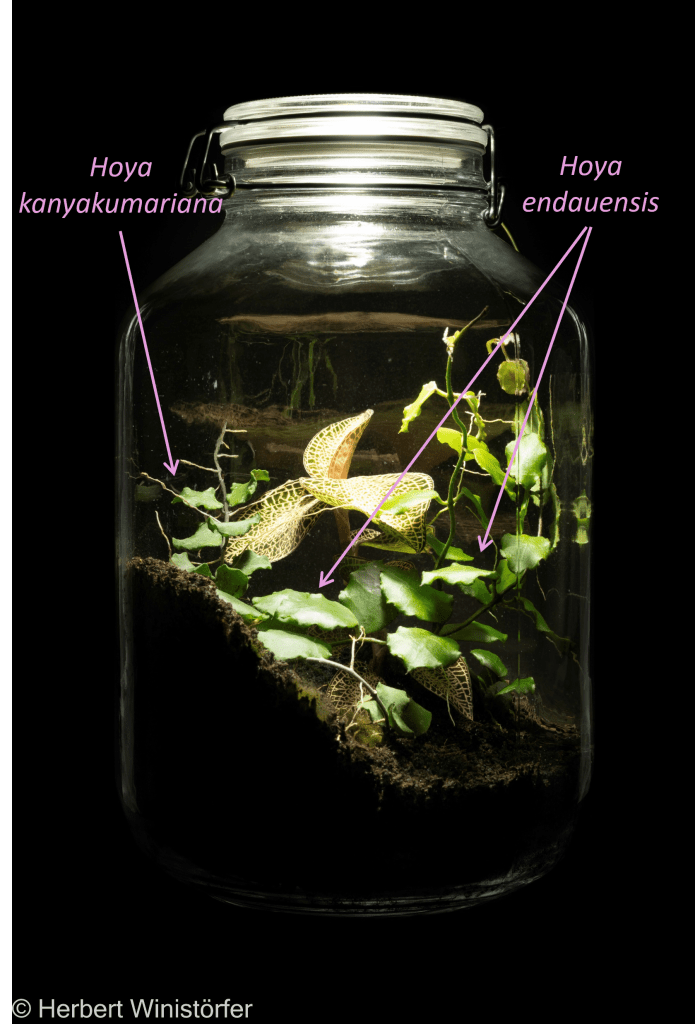

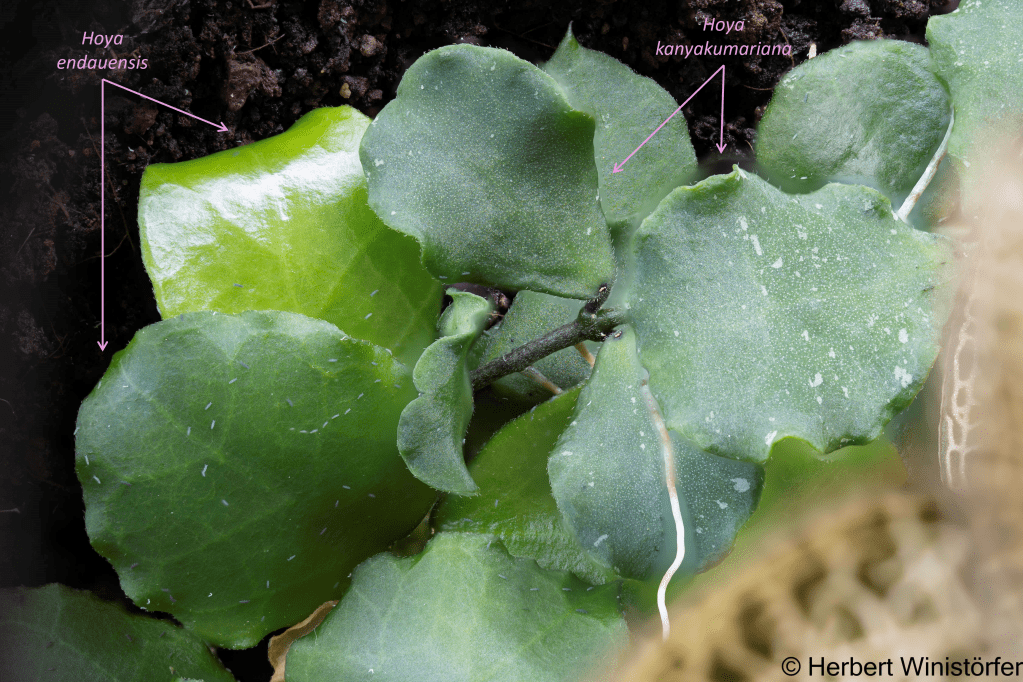

When I purchased Hoya kankakumariana from my local nursery, it came mounted on a piece of wood with sphagnum moss. I carefully dismounted it and removed all moss attached. It turned out there were three separate shoots of different lengths and with three to mine leaves each. I started a new container, placed the three shoots on the substrate surface and combined them with a jewel orchid. On occasion I showed pictures of my new build to a real Hoya expert, Jessica Ericsson-Hedlöf from The Swedish Hoya Society. She was interested in my attempt to grow Hoyas in the hermetosphere, but asked me whether I had considered that I might have two different Hoya species in that container. I had never done so, trusting completely in the label when I purchased the plant. But now I started diving into the literature, and it soon became obvious that she was right. One shoot with three leaves was H. kanyakumariana, the two shoots with more leaves were H. endauensis (see the picutre below). In the absence of flowers, the two can be distinguished by the shape of the leaf blades: H. endauensis has a more broad and round leaf blade while H. kanyakumariana has a very narrow base just where the petiole meets the leaf blade. How could I miss the difference?

After three months in the closed container, H. endauensis had grown massively, H. kanyakumariana less so, but both seemed to be happy with the conditions provided (see the picutre below).

On a close look, the different leaf shapes between th two Hoyas becomes evident (see picture below).

The flowers would provide definitive certainty about the identification of the two Hoyas, if it came to that. It did now, for H. kanyakumariana (see pictures below).

Surprisingly little information is available about H. kanyakumariana. The Global Biodiversity Information Facility GBIF, the largest database of specimens (preserved or observed in nature) provides not a single occurrence (GBIF Sekretariat 2024).

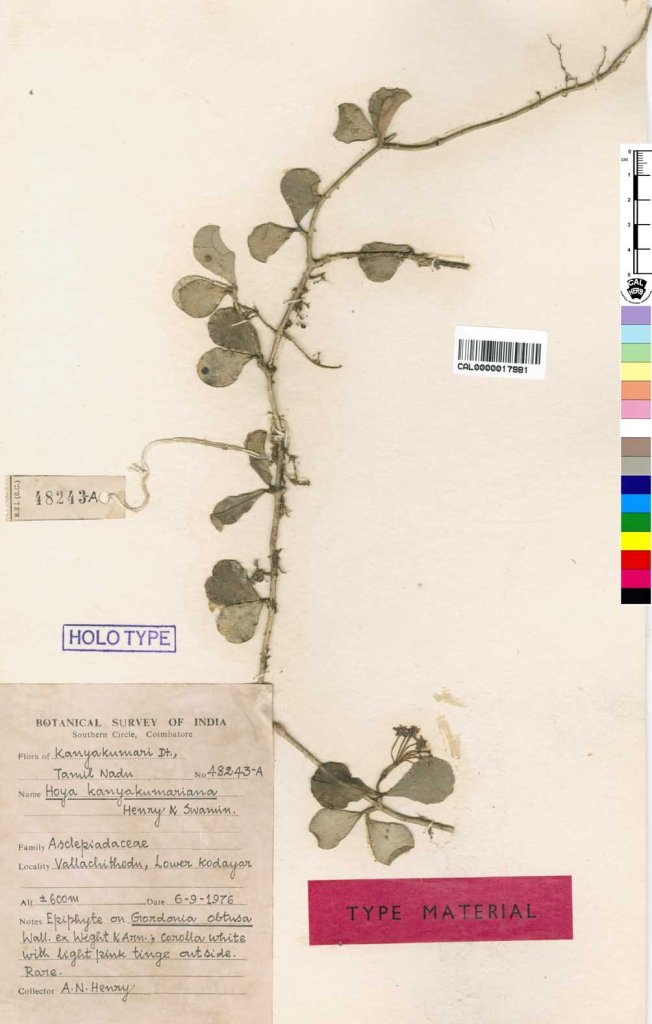

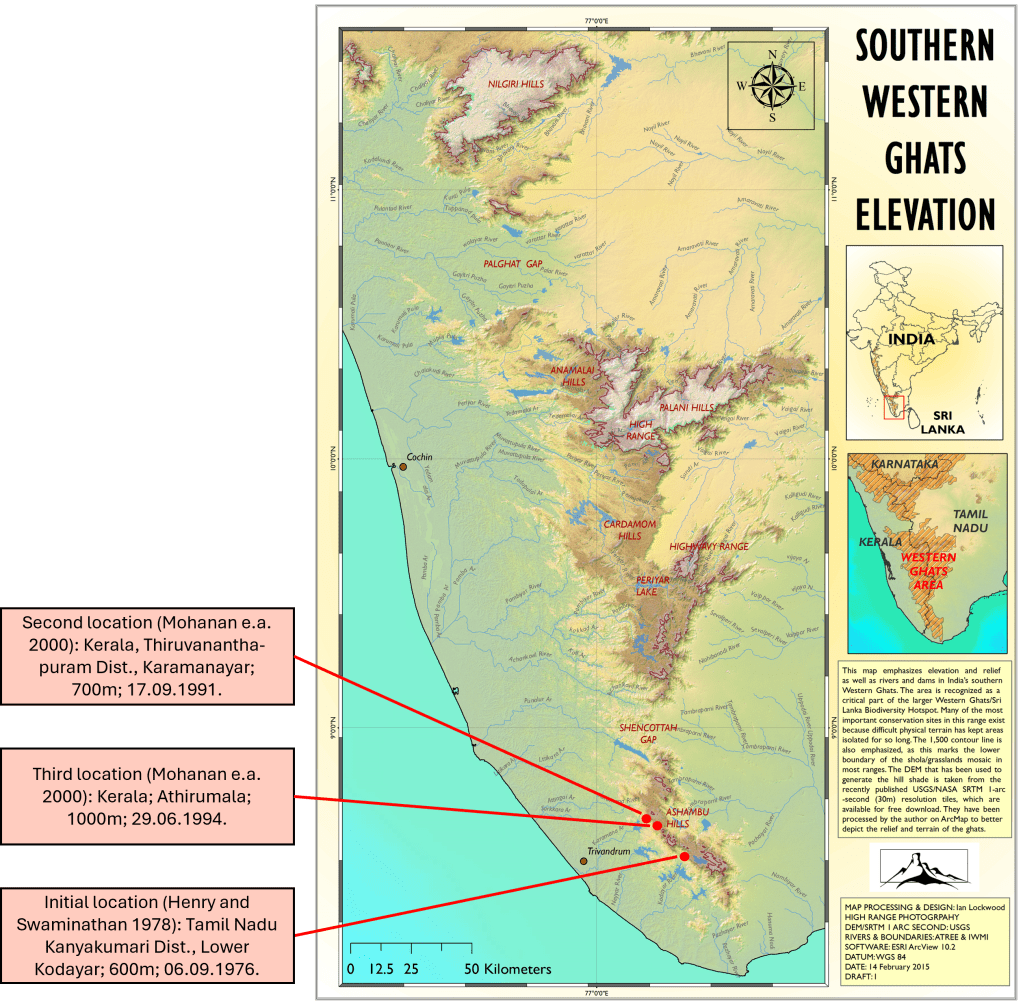

The species was scientifically described in 1979 (Henry and Swaminathan 1979), based on plant specimens found in 1976 in the southernmost foothills of the Western Ghats in Tamil Nadu province. It was named by the authors after the district of Kanyakumari at the southernmost tip of the Indian subcontinent, where it was found. Further occurrences are documented for 1991 and 1994 (Mohanan 2000) from the neighboring province of Kerala. The described specimens are stored in Central National Herbarium, Calcutta (Henry, holotype), Madras Herbarium (Henry, isotypes) and in Tropical Botanic Garden and Research Institute, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala (Mohanan), most of them being available to the public in digitized form (see the holotype below).

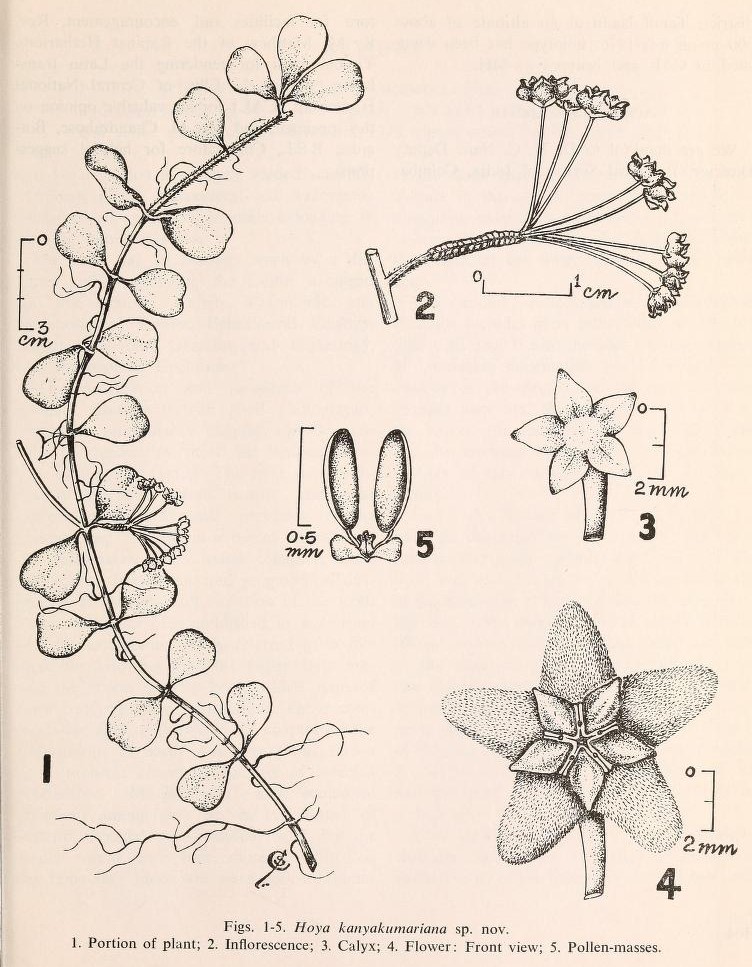

The drawings published by Henry and Swaminathan (1979) together with the initial description are even more informative (see below).

The map below shows the three known locations where H kanyakumariana was found, in the southernmost elevations of the Western Ghats, on the border between Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

The habitat is described as “evergreen forests and montane vegetation at altitude 500-1400 m” (Mohanan e.a. 2000) and “at an altitude of about 600 m” (Henry and Swaminathan 1978). According to the label on the holotype, the host plant is Gordonia obtusa, an evergreen tree endemic to the Western Ghats, bellonging to the tea family (Theaceae). However, no information is available on how specific the host plant selection is for H. kanyakumariana. The India Biodiversity Portal (Sasidharan 2024) as well as the Rare and Endemic Flora of Tamil Nadu (Selva Singh Richard 2020) list H. kanyakumariana as Critically Endangered.

The only pictures publicly available (according to my research) that show H. kanyakumariana in its natural habitat are from the database Eflora Kerala (2024) (see below).

The species has been commercially available as an ornamental plant in Europe since the late 1990s (Blom 2003: 14), is widely cultivated today and is readily available commercially. It is to be hoped that the limited natural habitat of this Hoya species will be preserved and that the species can thus be saved from extinction. Advice on the care of H. kanyakumariana is not rare, but rarely more than anecdotal and, moreover, varies widely. Two recognised experts on Hoyas state:

“It is a slow grower; avoid oversized pots. The plant does not like wet soil conditions and may easily rot in wet soil. The plant should be placed in a sunny, warm position. It can be grown without problems in dry air. H. kanyakumariana flowers any time during the year. It is easy to root and one node cuttings can be used. It does not take too long for the plant to reach flowering size.” (Wennström and Stenman 2008: 74)

As for me, direct sunlight and dry air is exactly what I can not provide. However, H. kanyakumariana did finally show its gorgious opened flowers exactly 382 days after the shoot cutting with three leaves has been placed in the closed container.