If hermetospheres are supposed to last over years, it is advantageous to work with plants that are able to produce offspring under the particular restrictions given (a.o. limited space, unlikely pollination). I have already been able to observe and describe two different kinds of second generation plants: Production of seed through self-pollination and spontaneous formation of ‘leaf cuttings’. The terrestrial orchid Ludisia discolor has its own way of ensuring offspring in the absence of pollinators. The key to this type of vegetative propagation lies in its rhizome. In botany, this is the name of “a root-like stem, lying horizontally on or situated under the ground, bearing buds or shoots and adventitious roots” (Hickey and King 2000: 36). Their rhizomes belong to the distinguishing features not only of Ludisia but the entire subtribe of Goodyerinae, the group of so-called jewel orchids (Juswara 2010: 17).

Shoots of Ludisia discolor initially grow upright and gradually form a rosette of (alternate) leaves. Older leaves die off, and where they were attached, the shoot loses its vertical orientation and lies horizontally on the substrate, becoming a rhizome. Only the youngest part of the shoot remains vertical and eventually forms an upright inflorescence. After flowering, this dies off. The rhizome becomes fleshy and out of it grow roots on the one hand and new shoots, the next generation, on the other.

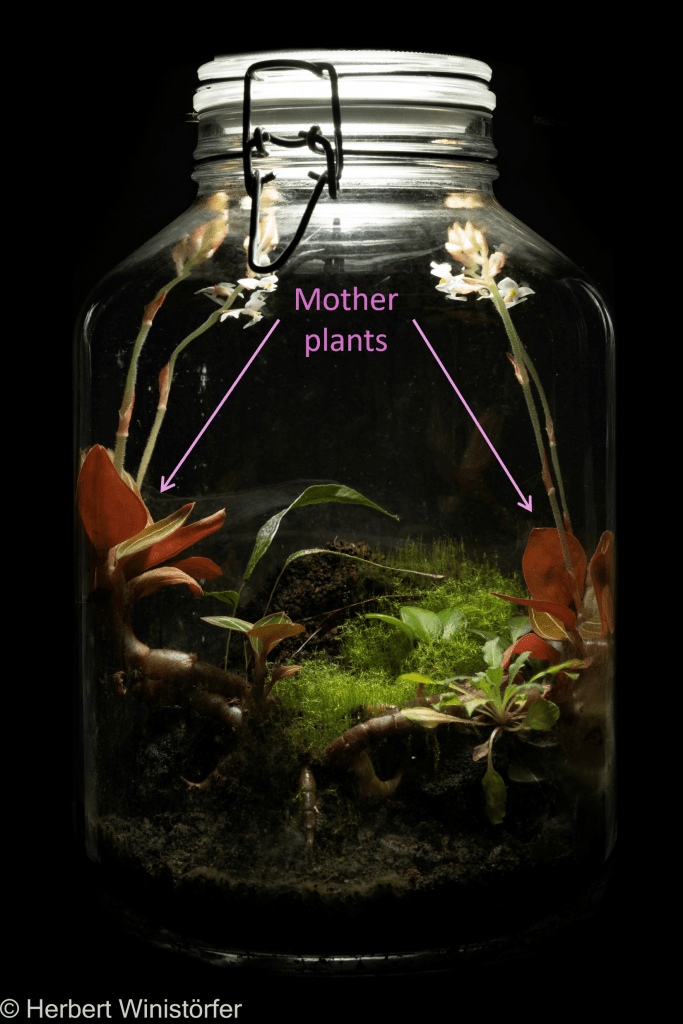

The pair of picures show the initial mother plants of Ludisia discolor in my hermetosphere while flowering and their daughter plants six months later.

And here is a 360° view of the container.