In my experience, many tropical spike mosses are well suited for closed terrariums. Some spread so quickly with the help of rhizophores that they crowd out other plants as long as nutrients are available. Selaginella brooksii, on the other hand, grows rather slowly. Propagation is simple – it is sufficient to place a shoot, preferably one with rhizophores, on the substrate. In the warm and humid environment of the hermetosphere, it will most likely root and continue to grow.

The video below gives a 360° view of a closed container of five litres with plants from Borneo about six months after the start. Selaginella brooksii, growing from the slope, has grown considerably, but does not (yet) pose a threat to the other plants.

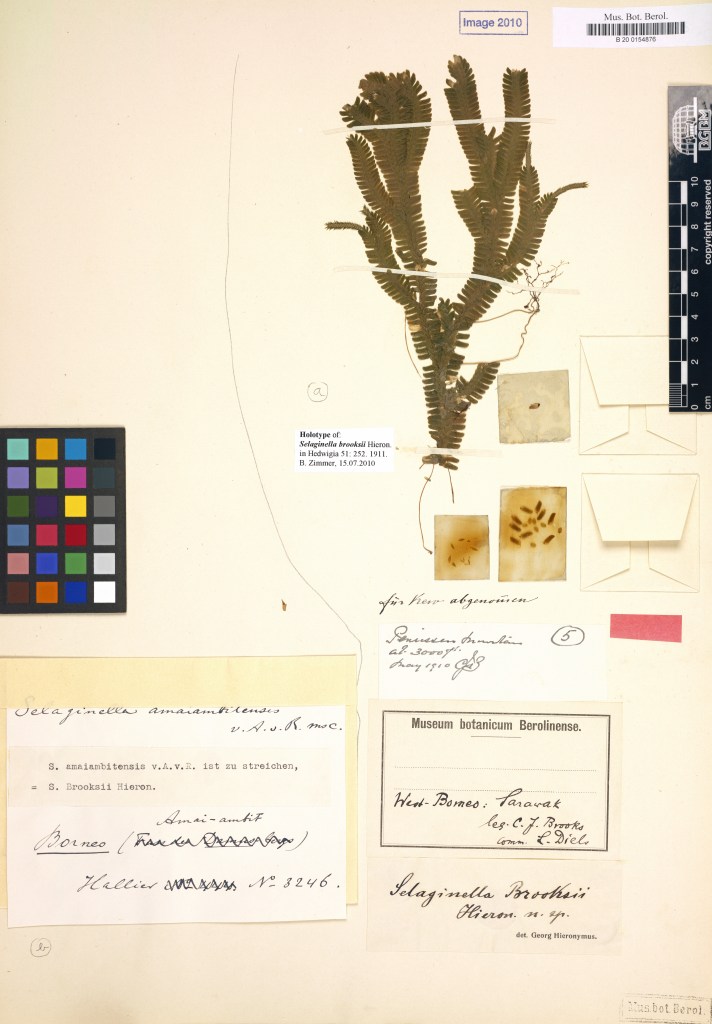

The three pictures below show a time series over the initial six months. This allows the speed of growth to be estimated. In this Selaginella species, the vegetative shoots are very easy to distinguish from the spore-bearing parts. These so-called strobili grow at the end of the branches and are significantly narrower than the vegetative shoots (see the herbarium specimen at the bottom of this post). So far, no strobili have grown on my plants. I assume that the growth of a branch comes to an end with the formation of a strobilus.

The history of the discovery and first description of Selaginella brooksii is, as is often the case with tropical plants, also a history of colonial activities by European states. The story of S. brooksii is far from unique, but it is exemplary and therefore worth telling here.

The colonial context

The story unfolds between 1893 and 1912, at a time when the island of Borneo was divided into four spheres of influence (see the map below from 1901). Along the north-western coastline, from NE to SW, were British North Borneo, the Sultanate of Brunei and Sarawak; the southern and largest part of the island was Dutch Borneo.

“As European influence expanded in insular Southeast Asia throughout the early modern era, colonial interests shifted from maintaining favorable trade zones along the coasts and rivers to an increasing control of territory and its human populations. The island of Borneo entered the colonial ambit relatively late in this process, but its eventual division between British and Dutch spheres of influence and control has had profound consequences for the peoples that fell under either. There and elsewhere, territorial boundaries sliced across well-established networks of communication, trade, common traditions, and strong ties of kinship.” (Wadley 2001: 623)

“In the 1840s the Englishman James Brooke had settled in Sarawak in north-west Borneo. Sarawak was recognized as a separate state by the United States in 1850 and by Britain in 1864. Brooke had first arrived there in 1839, ostensibly to explore and to carry out scientific research, during the uprising [of pirates and native peoples] against the Sultan of Brunei. Brooke helped to suppress the rebellion and was offered the governorship of Sarawak by the Sultan of Brunei’s uncle, Muda Hashim. Dutch concern mounted, however, as it became obvious that Brooke’s aim was to establish permanent British influence in north-west Borneo.” (Mead 2001: 28) James Brooke was appointed Rajah of Sarawak by the Sultan. He and two of his heirs ruled Sarawak until 1946. The three are still called the White Rajahs today.

“After James Brooke established his kingdom, the Dutch sought to define and demarcate the boundary between their respective claims to western Borneo. However, they were frustrated by the continued movement of people and trade across the inter-colonial border. This frustration was particularly acute along the portion of the border that partitioned the large Iban population. The Iban defied both colonial powers in refusing to end their headhunting practices, pay imposed taxes, and seek permission to move across the border.” (Wadley 2001: 624)

“Following James Brooke’s progress, in the 1840s, in building his private estate in Sarawak, the Dutch in Pontianak, on Borneo’s west coast just south from Sarawak, were hard-pressed to begin driving military expeditions into Borneo’s hinterland. After confronting defiant sultans and warlike independent upriver tribes, they were able to control the coasts and the trade from major river drainages. Before long, they recognized, however, that actual territorial control was needed, complete with administrative and military structures and set international boundaries and, in the closing decades of the nineteenth century, major expeditions were launched to hitherto unexplored remote regions, […] till, by the 1930s, the whole of the island’s southern interior regions had come under actual Dutch control and administration.” (Sellato 2024: 2)

A Dutch excursion to the upper reaches of the Kapuas River 1893-1894 leads to the first collection of S. brooksii.

As far as we can know, the first scientific collection of S. broksii took place in April or Mai 1894 by the German botanist Hans Hallier on a mountain called Amai Ambit. From 1893 to 1897, Hallier was a scientific assistant at the Buitenzorg Botanical Garden on Java, where he was partly employed as a Dutch civil servant. He later worked at the Botanical Institute of the University of Munich and at the Botanical Museum in Hamburg.

The circumstances of the journey are well documented and best described in the words of its head Anton Willem Nieuwenhuis (1904: chapter 1, translated from German with the help of deepl.com): “In 1893 and 1894, the [Society for the Promotion of Scientific Research in the Dutch Colonies] organized its first major scientific expedition to Central Borneo; it was significantly supported by the then resident S. W. Tromp of the “Wester-Afdeeling” of Borneo, who understood very well that an expansion of knowledge of the country and its people would also be of great political importance.

The participants in the expedition had been given the task of advancing from the west coast through the previously unknown areas of the upper Kapua and upper Mahakam to the east coast and, during the journey, to collect as much scientific material as possible and to study the population. In Kutei, however, warning voices were soon raised, drawing attention to the great dangers of such an undertaking; therefore, the initial plan was abandoned and the expedition limited itself to exploring the river area of the upper Kapua, where rich botanical, zoological, geological and ethnological collections were made from November 1893 to October 1894. Thanks to the support of the government in the form of protection and transport, the researchers were able to work separately, each in his own field; while the zoologist Dr. J. Büttikofer and the botanist Dr. H. Hallier settled in the jungle, the geologist Prof. G.A.F. Molengraff traversed extensive stretches of land in order to get to know their formation and ended his journey with a successful journey from Bunut south to Bandjarmasin. While everyone enjoyed the necessary freedom of exploration in this way, I, as the expedition doctor, was responsible for managing the whole thing. As my medical assistance was rarely required by the members of the expedition, I was able to stay in the villages of the natives and take care of the supply of new provisions and the recruitment of coolies from there.”

The political dimension of the excursion is explicitly mentioned here and further clarified by Sellato (2024: 15): “Solco Walle Tromp, the resident (governor) of West Borneo, wanted to control the narrow east-west corridor […] between the sources of the Kapuas and Mahakam […] and the Rajang river basin in Sarawak, in the north, from where they felt they had reasons for suspecting the Brooke raj of contemplating an expansion of its possessions […].” In order to be able to exercise control over a hitherto largely unknown area, it must first of all be explored. This was the purpose of the state-funded excursion.

As a result of his collections, Hans Hallier sent a herbarium of 3450 numbered sheets and numerous living plants preserved in spirit to the Buitenzorg Botanical Garden (today: Bogor) on Java (Hallier 1895: 448 f.), where he worked as a temporary assistant from 1893 to 1896 after completing his doctorate. Among the herbarium sheets was the spike moss with the number 3246, which was later described as Selaginella brooksii. Hallier had already surmised that the scientific processing of the plants he had collected would take years. He himself travelled back to his Dutch homeland as early as 1896. From 1905, his fellow countryman C.R.W.K. van von Alderwerelt van Rosenburgh (1863-1936) worked in Buitenzorg. As an expert on ferns and fern-like plants, he sifted through the relevant parts of Hallier’s collection. He presumably wrote a note on the sheets with the number 3246, which refers to the plant as ‘Selaginella amaiambitensis v.A.v.R.’ (see the herbarium specimen at the bottom). However, a corresponding scientific description was never published, so the name never became valid.

A British excursion to Mount Penrissen in 1910 leads to the second collection of S. brooksii.

Now that we know that the Dutch excursion was largely politically motivated on the part of the Dutch authorities, we will see that the second collection in 1910, this time on the British-controlled side of the border, was largely driven by economic interests.

What we can know of the collector is best taken from his orbituary, published in 1955 in The Entomolgist (A.G.G. 1955): “Cecil Joslin Brooks was born at Cambridge […] on May 7, 1875. He was educated privately, studied chemistry at King’s College, London, and became chemist to the Sussex Portland Cement Company and later chemist and departmental manager to a smelting and desilverizing works, where he carried out research in new process work. In 1900 he proceeded to Sarawak, N. Borneo, as an assistant to the Borneo Company and worked on their gold extraction plants. He soon became very interested in the tropical fauna and flora of the island and commenced to collect butterflies, moths and ferns in his spare time. He also made collecting trips to the mountains of Upper Sarawak in search of rare specimens, especially ferns, in the study of which he was greatly assisted by Mr. John Hewitt, at that time the Curator of the Sarawak Museum. In 1912 he went to Sumatra as metallurgist to a mining company, where he stayed for 12 years, continuing to add to his collections as opportunity offered. […]. He died at Hampstead on March 17, 1953, after a long illness.”

In order to understand the economic and political context of C.J. Brooks’ work in Sarawak, it is important to understand the significance of his employer, the Borneo Company. Since the early nineteenth century Chinese miners had been mining gold in the westernmost part of Sarawak. A dispute over taxes levied by the Rajah’s administration on opium consumed by the Chinese led to an uprising in 1857. Its violent suppression by the Rajah’s forces had far-reaching consequences. It led to the collapse of the Chinese mining industry in Sarawak, strengthened the Rajah’s position and finally led to the taking over of mineral exploitation in the state by the Borneo Company. The Borneo Company Ltd., established in London in 1856 with a market capitalization of some 60,000 pounds, was later to emerge as the most powerful monopolistic concern in Sarawak. With its superior technology and capital, and by virtue of its special relationship with the Brookes, the Company took over gold mining in Sarawak (Kaur 1995: 74ff.). In 1879 it was given the right to work all Sarawak’s gold mines and, prior to 1895, paid no royalties. In I898, the Company introduced an innovative method of extracting gold ore by the cyanide process. Between 1899 and 1921, its Bau and Bidi operations produced 983,255 troy ounces of gold, worth $25.9m (Sunderland 2015: 5). The Brooke administration opened the country to the interests of western capital and geared the economy to the exploitation of Sarawak’s mineral and other natural resources (Kaur 1995: 73), and the Borneo Company was certainly one of the main players in realising this plan. We can assume that C.J. Brooks’ natural history excursions, including the one to Mt Penrissen in 1910, were not conducted on behalf of the Borneo Company. Nevertheless, they would not have been possible without the latter.

Brooks published a short report of his excursion to Mt Penrissen in 1912, together with a list of ferns found there. In it he mentions the collection of spike mosses (Brooks 1912: 39): “In a collection of five species of Selaginellas determined by Professor Hieronymus four proved to be new to science.” We can assume that S. brooksii is among them, because the first description of our Selaginella was published without delay. Georg Hieronymus had a special interest in Selaginellas and writes about the source of the plant material (Hieronymus 1912: 254): “The species was collected by C.J. Brooks on the Penrissen Mountains in British West Borneo (Sarawak) at an altitude of 3000 feet above sea level in May 1910 (No. 5).” In the same publication, Hieronymus, from 1892 curator of the Botanical Museum at the Botanical Garden in Berlin, mentions to have named the plant in honour of the collector C.J. Brooks and to have received Brooks’ Selaginellas from Prof. Dr. Ludwig Diels in Marburg. Diels himself was appointed director of the Botanical Garden in Berlin in 1921 (Pilger 1921). How Brooks’ Selaginellas came into his possession could not be resolved.

When we enjoy the diversity of tropical plants today by cultivating them, we should not forget the dubious circumstances under which some of them found their way to us.