Only rarely do I use plants in my closed containers that can grow much larger in nature than what I can offer them. I acquired the fern Selliguea albidosquamata as a piece of rhizome with three small, simple leaves with entire leaf blades. Only later did I realise that I got a very young plant and the adult fern can form fronds up to 1m long with up to 18 pairs of pinnae. For a range of habit see the three herbarium specimens shown below.

Now that my fern has been growing in the closed container for more than six months, I can say that it is slowly but steadily forming new fronds and seems to be coping well with the conditions. On closer observation and comparison with pictures of other specimens, I noticed one aspect in particular: My fern shows a large number of white dots on the margins and upper side of the leaves formed in the glass. Other specimens showed these white spots only or almost only on the leaf margins (see example below). So I began to take an interest in these structures, which apparently caught the eye of Carl Ludwig von Blume as early as 1827, who chose the species-specific epithet after them (albido-squamata = white-scaled), when he first described the fern as part of his flora of Java (Blume 1827: 132). What are these spots and is there an explanation for the fact that they are exceptionally numerous and pronounced in the closed container?

The structures are called lime dots. They represent one of several manifestations of so-called hydathodes. Hydathodes are widespread in the plant kingdom and are organs for the secretion of water and the salts dissolved in it. They usually occur where leaf veins end. The nerves are dilated there and end in a specialised tissue connected to the leaf surface or the leaf margin, which can secrete liquids through the epidermis or stomata-like pores (Mehltreter e.a. 2022: 331). This process is called guttation. When the water evaporates on the surface, salt crystals remain at the edge of the pores, which are visible as white deposits. Their composition varies depending on the species. In the case of ferns, they are mainly calcium salts and silicon salts (Mehltreter e.a. 2022: 341).

Guttation may happen passively when water is forced through pores by positive xylem pressure, or actively driven by a still unknown energy-consuming process in the hydathode cells. Various assumptions have been made about the physiological benefits of this process. For plants in regions with high humidity, guttation supposedly maintains a minimum xylem flow to allow a continuous supply of mineral nutrients to the peripheral parts of the plants when transpirational pull is low or absent (Mehltreter e.a. 2022: 332).

But why don’t all plants have hydathodes and how can the differences be explained? It is considered certain that the ability to form hydathodes is genetically determined and hereditary. In the course of evolution, the property has been acquired and lost numerous times independently. Only recently has some light been shed on the situation in the group of ferns. According to Mehltreter e.a. (2022: 336f.) hydathodes are present in 92 fern genera and >10 % of all 10 578 known fern species (as per 2016). Their distribution in 19 families (e.g. Equisetales, Polypodiales) and presence/absence within certain genera (e.g. Pyrrosia) indicate multiple origins and secondary losses, especially during the last 50 million years of fern evolution. Differences between hydathodes of closely related fern species, such as the production or lack of salt residues (e.g. within Aglaomorpha), their presence in young but absence in mature leaves (e.g. Pyrrosia nummularifolia), and complete versatility within the same species (e.g. Cryptogramma stelleri), may indicate genetic mutations, changes during an individual’s life span or functional changes triggered by environmental factors, respectively.

In a study based on the distribution data of 477 fern species along a tropical elevational gradient of 3300 m altitude in Costa Rica, Kluge and Kessler (2007) found that 116 species (24.3%) possess hydathodes. The presence of hydathodes was strongly correlated with elevation and humidity, with highest percentages of ferns with hydathodes occurring in species assemblages of cold, humid environments. It is likely that in environments with high and constant air humidity the evaporation of water is hindered by high ambient air humidity, and hydathodes may compensate for this disadvantage.

How does all this apply to my S. albidoaquamata? The species belongs to the Polypodiaceae family where hydathodes are widespread (Mehltreter e.a. 2022: fig. 3). Its natural habitat are tropical primary and secondary forests, scrubland, disturbed sites etc., often near streams, at alitudes between sea level and 3500 m.a.s.l., where it lives as an epiphyte, epilithe or terrestrial, common in most localities (Hovenkamp 1998: 46). It seems plausible that the ability to form hydathodes can be advantageous for this way of living.

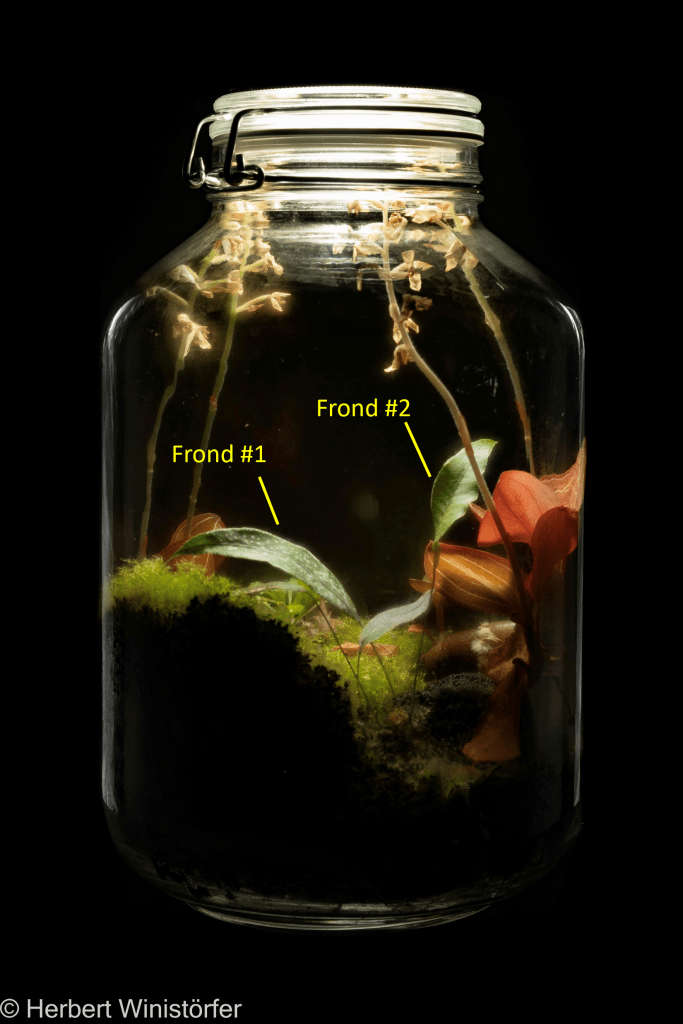

From my six months experience with the fern in the closed container I can tell that hydathodes are present in young but fully expanded fronds, and lime dots develop during the following weeks. The pictures below show two subsequent fronds labelled frond #1 and #2 on the rhizome of S. albidosquamata in an container of 5 litres. On the older frond #1 (~11 weeks old), white salt residues (lime dots) are numerous both on the leaf margin and on the upside of the leaf blade. On frond #2 (~5 weeks old and recently fully developed) the developing hydathodes can be recognized as tiny bright spots, also here both on the leaf margin and distributed over the upper side of the leaf blade.

Because guttation could be observed (see the image below) at the leaf margins, it can be assumed that the hydathodes of frond #2 are actually active in the hermetosphere.

Could it be that the especially high number of lime dots that the fern forms in the hermetosphere are an acclimation reaction to the particularly high relative humidity in the closed container?