This fern is not only visually very appealing, it also has other characteristics that make it an ideal plant for hermetospheres: small size, slow growth and a preference for a permanently warm and humid environment. The fact that it is widespread throughout tropical America indicates that it does not make any exceptional demands in order to thrive. Other than a lot of trendy terrarium plants, this one is known in modern science for over 300 years. Long before the plant received its current name Microgramma lycopodioides it was named by an early modern scientist and traveller as “Climbing stag’s tongue with scaly stems”. This is a good example of how European naturalists proceeded when they were looking for ways to explore and describe the tropical plant life of the New World. If you are interested in the story of Frère Charles Plumier, read to the bottom.

Microgramma is a fern genus of c. 30 species, all occurring in the Neotropics except for one in Africa. They are epiphytes with long-creeping rhizomes, often growing from trunk bases to the canopy, with a few species also able to grow in rocky or terrestrial habitats. (Almeida e.a. 2021)

My experiences with Microgramma ferns in closed terrariums are mixed: While M. nana thrives for years in a container, M. vacciniifolia grew some hairy rhizomes but never proper leaves. It took me a surprisingly long time before I could lay my hands on a specimen of M. lycopodioides. Sometimes the most common plants are hard to come by.

Although the plant pictured here has only been living in the closed terrarium for about six months, I am confident that it will thrive permanently under these conditions. The long scales on the rhizome are a striking feature of this fern. Other features are the leaves patterned with dark veins and the two rows of dot-shaped sori on the underside of mature fertile leaves.

The pair of pictures below show the development of the fern in its container with a difference of 2½ months.

If one traces the history of the naming and description of tropical plants from the New World in modern literature, one usually gets no further back than the year 1753 and the epoch-making work ‘Species Plantarum’ by Carl Linnaeus. There, the majority of plants known at that time appears for the first time in the form of a binomial naming with genus name and a single species-specific epithet that is still in use today. It is easy forgotten that for the neotropical plants in his work, Linnaeus could build on the preliminary work of earlier naturalists who had travelled the New World, researched its plants and brought records back to Europe: preserved specimens, descriptions and drawings as well as the names given to new plants. M. lycopodioides is well suited to recounting this early phase of the scientific study of neotropical plants. My sources for this story are listed at the end.

In 1689, the French Franciscan monk Père Charles Plumier, aged 43, was one of the first European naturalists to arrive in the Antilles. Together with the physician Joseph Donat Surian, he had been commissioned by King Louis XIV to search for medicinal plants there. Plumier had studied maths and physics in Toulon and later theology in Rome. He was chosen because of his special knowledge of plants and his talent for drawing. On his return, the king was so impressed by the results that he appointed Plumier ‘Botaniste du Roi aux Antilles’ and three years later authorised him to make another expedition.

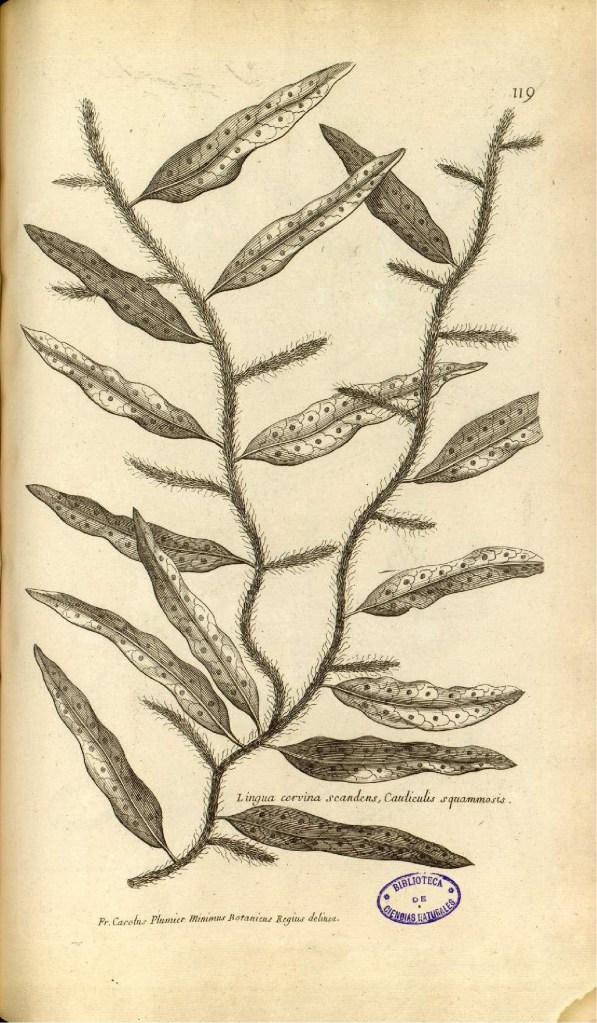

While most of the plants collected and prepared by Plumier have presumably been lost, his precise drawings and descriptions have found their way into the scientific literature. He published these in 1693 in his work ‘Description des plantes d’Amérique’. Here, the fern later called M. lycopodioides appears under the name ‘Phyllitis scandens, cauliculis squammosis’ (‘Climbing Phyillitis, with scaly stems’). At that time it was usual to assign plants to a genus, in this case Phyllitis, and to name the species with a few descriptive attributes. With a relatively simple drawing came a description in French. In my own translation:

“It grows a large number of very long and very slender stems which snake their way up the trunks of trees in the same way as ivy stems: These stems sprout a number of branches here and there, some very long and some very short; they are all covered with small, narrow, pointed scales, tanned and dotted with a number of small filaments, and from time to time they have alternate leaves on either side, about four inches long and seven or eight lines wide on the lower side; they have a wavy edge and taper towards the tip, which is a little blunt; their consistency is membranous. The front is smooth and of a beautiful green colour: the back has a rib all along which gives other very small and wavy ribs: between the space between these ribs, there is a round powdery and greyish wart. I have found them in several places on the islands of Martinique and Santo Domingo.”

Only a year later, an early mentor and friend of Plumier’s, Joseph Pitton de Tournefort (1656-1708), published his main work ‘Éléments de botanique ou méthode pour connaître les plantes’. The two were both raised in Southern France and had undertaken botanical excursions together in the French Alps. But unlike Plumier, Tournefort had never travelled to the New World. Tournefort included the fern from the Antilles described by his friend in his list of plants, kept the three-word species description but assigned the fern to a different genus, which he called Stag’s Tongue: ‘Lingua Cervinia scandens caulibus squammosis’.

On his third and last mission to the Caribbean (1695-1698), Plumier visited Guadeloupe, Martinique, Santo Domingo and the coast of Brazil. On his return, he wrote his work ‘Nova Plantarum Americanarum Genera’, published in 1703, in which more than 100 new genera were described. He also prepared his ‘Traité des Fougères de l’Amérique’, which was published in 1705, after his death. Our fern appears there under the generic name given by Tournefort with a detailed description in Latin and French and a detailed illustration (see below).

The fern’s leaves, their distinctive veination and the sori are described here in the following words (in my own translation). “They are membranous, smooth, of a pleasant green colour and raised all along the back by a small vein which leads to others on each side, all wavy and oblique enclosing a powdery, greyish wart in each enclosure they form.”

Plumier was invited to take part in a new voyage out to Peru, but the hardships he had endured on his previous missions undermined his health. Suffering from pleurisy, he died on 16 November 1704, near Cadiz, while preparing for the mission.

Linnaeus himself makes the transition from the polynomial name of the fern in 1737 (‘Polypodium frondibus lanceolatis integerrimis glabris, caule repente squamoso’) to the binomial name in 1753 (‘Polypodium lycopodioides’), in each case with reference to the works of Plumier and other authors. It is not entirely clear today which herbarium specimens, in addition to the available literature, served Linnaus as the basis for his descriptions.

The story told above is derived from the following sources: Cremers e.a. 2016, Cremers e.a. 2022, Genaust 1996, Hollsten 2012, Linnaeus 1737, Linnaeus 1757, Plumier 1693, Plumier 1705, Rouhan and Gaudeul 2013, Stearn 1958, Tournefort 1694.