The unequal growth of two leaves in a pair from a single branch node is called anisophylly. It occurs in several, non related groups of Angiosperms that have opposite leaves, like Gesneriaceae, Melastomataceae, Rubiaceae and Urticaceae and is therefore assumed to have evolved independently several times. But what is the competitive advantage of this trait for the respective plants?

A cultivated plant, that feels exceptionally comfortable in hermetospheres, can serve as example. I would even go so far as to say that if I were to choose just one plant for a container of 5 liters, it would be Triolena pileoides. The plant has the appearance of a miniature shrub with elongated leaves with serrated margins, of dark green colour on top and reddish on the underside. Solitary white flowers occasionally appear at the end of a branch, not much more than 1 cm in diameter, and stay open for just a single day. The characteristic, triangular seed capsules could not be observed in the hermetosphere because pollination of the flowers did not happen.

The plant was first described in in a monograph on the Melastoma familiy as Diolena pileoides (Tirana 1872) and later reassigned to the genus Triolena (Wurdack 1977). On the basis of molecular, geographical and morphological evidence, the genus was recently assigned to a new tribe Trioleneae, together with the genus Monolena (Bacci e.a. 2019). The genus Triolena now comprises 27 accepted species, all of which are native to the tropical regions of Central America and northeast South America.

The two pictures below show the development of Triolena pileoides in the hermetosphere within the first 28 weeks.

From the very early descriptions of this species (Tirana 1872, Cogneaux 1891) on, clear reference is made to the two differently sized types of leaves. So, what can we know today about anisophylly?

The following overview is based on a study by Muelbert e.a. (2010) as well as the literature cited therein. At that time important questions about the physiology, genetics, ecology and evolution of anisophylly remained unanswered, and hardly any further answers have been found since then.

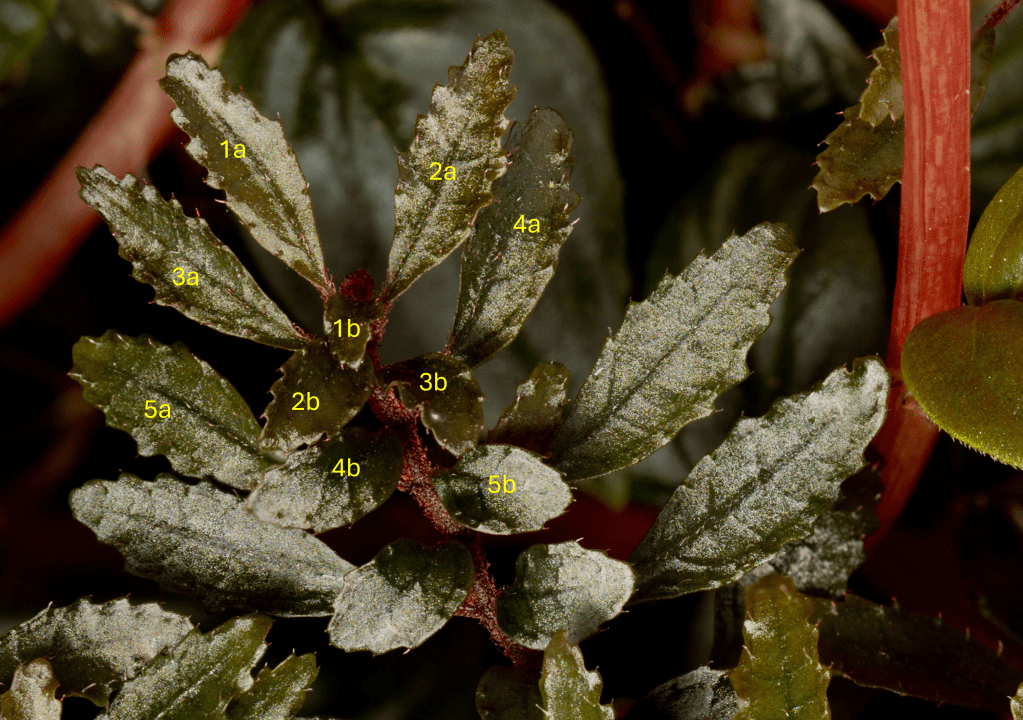

The way in which leaves are arranged on a shoot is often a characteristic feature of plant families. Families with a pair of opposite leaves from a single branch node are typically distributed in drier or more open habitats. However, several large plant families with opposite leaves are common in tropical rain forest understories. These include the Melastomataceae, to which Triolena pileoides belongs. Within the Melastomataceae of tropical America, anisophylly has been observed in species of Bertolonia, Blakea, Clidemia, Leandra, Miconia, Macrocentrum, Tococa, Triolena and Maieta. The degree of anisophylly varies greatly between species, and in some cases the smaller leaves may even fall off at an early stage of development or appear to be completely absent, giving the plant an apparent alternate leaf arrangement. While some species of Melastomataceae (e.g. of genus Clidemia) show anisophylly consistently, there are other species (e.g. of genus Miconia or Leandra) where there are large differences even within the same individual. The extent to which the trait of anisophylly is of use to identify species is therefore still controversial.

The great variation in anisophylly among species of the same genus was nicely demonstrated by the example of Columnea (Gesneriaceae). Species adapted to a lot of sunlight showed hardly any tendencies towards anisophylly, while some shade-adapted species showed the characteristic very distinctly (see figure below).

From the earliest documentation of anisophylly, it has been thought to be an adaption to dimly lit understory environments, yet there are no ecological studies dealing with anisophylly per se. The connection between leaf arrangement and light capture is obvious. Opposite leaves, where each pair is at right angles to the pair above or below it, were shown to be less advantageous than other forms as they increase self-shading due to the overlapping of the leaves. This could be demonstrated with the help of computer-based model simulation of light capture with different leaf architecture variants. Is this explanation sufficient?

One thing seems clear: the study of anisophylly as an independent phenomenon makes little sense. Rather, the adaptation of plant architecture to the light conditions in the tropical undergrowth is the result of a complex interplay of many different factors such as internode length, leaf size, leaf shape and leaf angle.