At first glance, the flowers of aroids (family Araceae) appear much less spectacular than those of other plants. Aroids are therefore loved by plant enthusiasts far more for their foliage than for their flowers. On closer inspection, however, the flowers offer amazing insights.

While tropical aroids have been popular as indoor, terrarium or aquarium plants for centuries, the genus Bucephalandra has only become widely known among hobbyists and gained corresponding economic importance in the last few years. Because Bucephalandra grow slowly, there is an incentive to collect wild plants and put them on sale. Bucephalandra is endemic to Borneo and the distribution areas of some species are likely to be very small. Therefore, wild collection for trade poses a serious threat to the species. Anyone purchasing a Bucephalandra should therefore ensure that the plant comes from greenhouse culture.

The natural habitat of Bucephalandra are river banks and other places that are periodically flooded by flowing water. Adaptations to these sites include very good root adhesion to the substrate, compact growth and hardy leaves. Plants with this kind of specialisation are called rheophytes.

So far 32 Bucephalandra species are scientifically described. These can look very different depending on environmental conditions. The assignment of the countless varieties offered in the trade under fantasy names to species is only possible for specialists, and mainly on the basis of the inflorescences.

I have been growing Bucephalandra in hermetospheres for about 1.5 years in containers of different sizes. I cover the bottom of the containers with lava pebbles and lava gravel and place the plants there so that the roots but not the rhizomes are covered with substrate. Unlike other hermetospheres (see Water Conditions), I fill up with water just to the edge of the substrate so that the roots of the Bucephalandra are permanently below the water line.

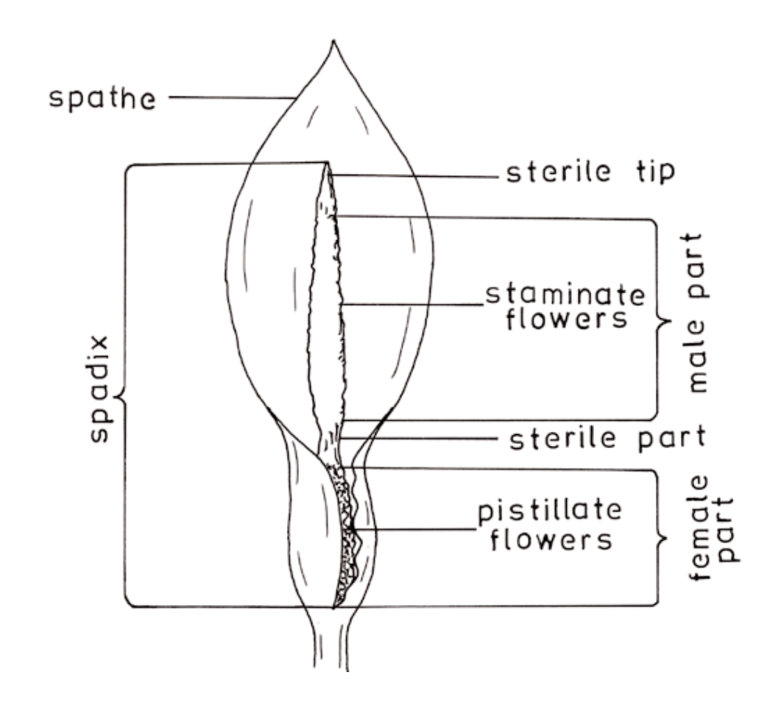

The figure below shows how the inflorescence of a typical aroid is structured. The same elements can be found in the inflorescences of Bucephalandra.

To understand how sophisticated the construction of the Bucephalandra inflorescence is, it is worth following the events in their chronological order. Chai and Wong (2019) have investigated this in detail for the species Bucephalandra muluensis in Mulu National Park (Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo). Its inflorescences are c. 3 cm long, about twice the size of the Bucephalandra in my container. However, the procedure described below is likely to be similar. Information for the paragraphs below is also taken from the following sources: Boyce and Wong 2015, Cusimano e.a. 2011, Nugraha e.a. 2022, Wong and Boyce 2014. For pictures of the different phases see the figure at the bottom of the post.

The flowering period lasts two days. All starts in the afternoon of the first day, around 1 pm. The timing during the day is most likely no coincidence. In the studied area, many different closely related species compete for the same insect pollinators. Some open their flowers as early as 4 am. The later moment of flower opening allows Bucephalandra muluensis to avoid the big competition. First, the female (pistillate) flowers (14±2 in number, each less than 0.5 mm in diameter) in the lower part of the cob (spadix) open, and the tip of the cob gives off a scent specific to the plant species, which attracts the pollinating insects suitable for the species. In the case of Bucephalandra, these are often fruit flies from the Drosophilidae family. At the same time, the bract (spathe), which completely encloses the spadix, opens to a narrow slit of about 2mm. The gap is just wide enough for the fruit flies to fit through and enter the spathal chamber. Little above the female flowers, the spathal chamber is narrowed, allowing only insects of a certain size access to the lower chamber during flowering of the female flowers. Fruit flies that had visited other inflorescences before now pollinate the female flowers. For this specific species, it remains to be found out whether the flies derive an advantage from visiting the flowers, or whether they have merely been deceived by the plant through the attractive scent.

The phase of female flower receptivity ends around 4 pm on day 1. Shortly afterwards, the narrow access to the female flowers is closed. This is done by movable shields on a few sterile flowers, which lie exactly at the narrowed point of the spathe between female and male flowers. By the way, these motile shields (see figure below, F-H) are the trait that distinguishes the genus Bucephalandra from all other genera. Only on day 2, again in the early afternoon, do the pollen-bearing male (staminate) flowers above the now closed constriction open (14±2 in number, each c. 1 mm in diameter). The flies that stay in the spathal chamber or now enter are loaded with pollen from the stamens. The spatial and temporal separation of the mature male flowers from the female ones prevents self-pollination from taking place. This contributes to the genetic diversity of the population. After only about three hours, the functional phase also ends for the male flowers. The upper part of the spathe is shedded and so insects leave the inflorescence, free to pollinate flowers that ripen the next day.

After successful pollination, the movable shields on the sterile flowers, that previously blocked the entrance to the lower part of the the spathal chamber, now become green and help protect the ripening berries. This process takes about one month. Berries are then released and transported by water currents. Thus, the distribution of the fruits is also perfectly adapted to the plant’s habitat at the flowing water.

The following figure shows the different stages of flowering of Bucephalandra muluensis in detail.

One response to “Tiny flies find tiny flowers”

[…] As with other groups of tropical plants that are of interest to the trade (e.g. Bucephalandra), the diversity of traded varieties and cultivars exceeds the range of scientifically described […]

LikeLike