This post is part two of a three-part series discussing water conditions, nutrient conditions, and light conditions in hermetospheres.

In a closed system of plant life, water, carbon and nutrients are subject to cycles. In the case of nutrients, dying plant tissue is beeing decomposed by bacteria and fungi, and the nutrients it contains are released, i.e. mineralized, and made available for uptake by roots for new plant growth. The key questions for success are:

- How much nutrients are initially given into the system? The initial position here is, that less is more: For once, undernutrition can be corrected relatively easy by nutrient supplementation while overnutrition is virtually impossible to correct. In addition, we tend to aim for slow growth and plants that tend to stay small; this is another reason to avoid over-supply of nutrients.

- In what form are the nutrients supplied to the system? Three forms are possible in principle: a) as living plants, b) as organic material in the substrate, c) as mineral salts available to plants in the substrate.

Even if a hermetosphere is initially set up with full planting, a nutrient deficit will occur if the substrate does not provide replenishment as long as dead plant material is not yet fully mineralized. I prefer to start with just a few young plants (see example below) to watch them develop and take possession of the landscape provided. Especially in this case, nutrient deficiency can become an issue. To prevent this, the nutrients necessary for the formation of additional plant biomass must be present in the system.

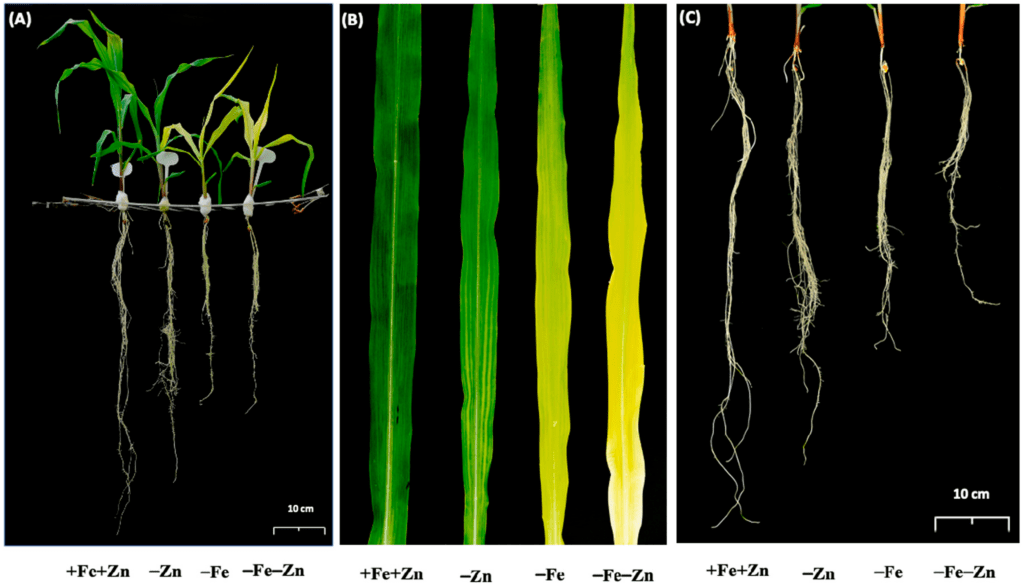

There are some basics on plant nutrition that plant growers should be familiar with: the distinction between macro and micro nutrients; the difference between mobile and immobile nutrient ions; deficiency, sufficiency and toxicity ranges of nutrient concentrations; the law of the minimum; and the role of soil acidity for nutrient availability to plants. The www is full of information but – as always – it is not easy to find facts that are reliable and understandable in the same time. My best source in that sense is an educational brochure by Montana State University from 2009. It also provides useful descriptions and illustrations of common nutrient deficiency symptoms. One symptom caused by lack of iron, zinc and other minerals is chlorosis: a yellowish-pale discoloration of leaves. Iron is essential for the production of chlorophyll.

Some plants in my early hermetospheres (set up 18 months ago) are by now showing signs of chlorosis (see below), so I have started to carefully supplement the nutrients with liquid orchid fertilizer and am now watching the effects. So far, this is based on trial and error, but is there not a more systematic approach?

For future hermetospheres I was wondering how much nutrients I would need to initially add to my 5l container to prevent damage to my plants from lack of nutrients. This was the time when I had to make some measurements to better understand my substrate. They helped me establish a mass and volume balance of an average substrate layer of lava granules (2-5mm) that reaches a height of 8cm in my 5l container, under the condition that no standing water remains at the bottom. I was surprised to realize that the dry lava accounts for 86% of the mass but only 51% of the volume in my substrate, leaving 21% to adhering water and 28% to air (see table below).

| kg | % mass | cm3 | % volume | |

| Substrate (dryed at max. 40°C) | 1.890 | 86.0 | 763 | 51.3 |

| Water adhering to the substrate | 0.308 | 14.0 | 309 | 20.8 |

| Air in the interstices | 0.000 | 0.0 | 416 | 27.9 |

| TOTAL | 2.198 | 100.0 | 1´488 | 100.0 |

The above mass and volume balance forms the basis for the next steps. The calculation below begins with the minimum soil nutrient concentrations for healthy plant growth, which are the nutrient requirements for my substrate (column 2). The mineral lava substrate will release certain nutrients over time (column 3). The difference between the nutrient requirement and the nutrient release is the nutrient deficit (or, in the unlikely event, the surplus), which must be corrected – relatively (column 4) and for my absolute substrate amount (column 5). These values are compared with the absoulte nutrient content of the living biomass of a fully vegetated tank (column 6). The following data were used or assumptions were made:

- To get an idea of the plant-available nutrient concentration of “fertile” soil, I used information provided by the Bavarian State Institute for Viticulture and Horticulture in a Guide to Fertilization in the Garden (Meinken 2021). For different soil qualities (light, medium, heavy) and each of the relevant nutrients, it distinguishes five classes of nutrient concentrations from A (very low) to E (very high). The values chosen for column 2 represent the lowest values for class C (sufficient/optimal) for light (i.e. sandy) soils. Do these values have any significance for natural soils in the tropics? Astonishingly little is known from nutient stocks and flows in natural tropical ecosystems. A nice overview is given by Proctor (2005). He shows exemplary data on two soils (0-10cm deep) from tropical rainforests in Costa Rica and Brazil, respectively. There, the concentration of plant-available K and Mg is in the same order of magnitude as in column 2 (between a factor of 0.3 and 2.3), for P somewhat lower (factors 0.05 and 0.12, respectively).

- To make an estimation of the amount of nutrients released by my substrate (column 3), a study carried out by Zaharescu e.a. (2019) provides useful data. The authors allowed different rock types (basalt, rhyolite, granite, schist) to weather for two years under controlled laboratory conditions (a.o. with microbe and plant growth) and analyzed the plant-available nutrients in the systems. To the values for basalt, that represent best my lava substrate, I added a factor 0.1 as the substrates used for the study were of ten times lower particle size (0.25-0.50mm).

- The input values for the nutrient content of a fully vegetated container (column 6) are the round base area of my 5l glass container (17cm diameter, 0.023m2); the nutrient content per dry weight of plant biomass taken from Schulze e.a. (2019 p. 209); the leaf dry mass per unit leaf area (LMA) assumed as 48g/m2 (Poorter e.a. 2009, average of the two values for ferns and herbs) and finally the assumption that a fully vegetated container has an average of two layers of leaves over its entire base area and one additional “layer” of root biomass.

| 1) Element | 2) Minimum soil nutrient concentrations [µg/g] | 3) Nutrients released by lava substrate over 2 years [µg/g] | 4) Relative nutrient deficit [µg/g] | 5) Absolute nutrient deficit for 1’890g substrate [mg] | 6) Nutrient content of a full vegetation [mg] |

| N | 11 | 0.00 | -11.29 | -21.34 | 49.03 |

| K | 33 | 2.02 | -31.19 | -58.95 | 32.68 |

| Mg | 70 | 3.39 | -66.61 | -125.89 | 6.54 |

| P | 44 | 1.30 | -42.36 | -80.06 | 6.54 |

| Fe | n.a. | 1.49 | n.a. | n.a. | 0.33 |

| Mn | n.a. | 0.16 | n.a. | n.a. | 0.13 |

The results are remarkable in several respects. Although lava, often chosen as mineral substrate for its physical and chemical stability, is generally considered to be inert (of low reactivity), the weathering process over two years is expected to release nutrients. These, however, account for less than 10% of the nutrient concentrations necessary to make lava a fertile soil. Among the nutrients considered, nitrogen (N) deserves special attention for several reasons:

- In terms of chemical composition of plant biomass, nitrogen is the most important plant nutrient with about 1.5% of dry leaf biomass.

- Nitrogen occurs in many different chemical compounds, two of which are suitable for uptake by plants: ammonium (NH4) and nitrate (NO3).

- As nitrogen is hardly released by rock through weathering processes, the main sources of plant-available nitrogen in soils are humus (organic compounds as a result of biomss decomposition), microbes able to process nitrogen from the air under special conditions as well as rain and dust from above. With a lava substrate free from humus, the only soucre of nitrogen in my system is the plant biomass of the initial setup.

If I do not want to start my container with full vegetation, what can I do to have the desired amount of nutrients in my initial setup? The following list is based on rumors from the community and pure speculation of mine.

- Add organic material: In theory, everything is possible between organic litter and fully developed humus; however, organic material in a high-humidity environment always has a tendency to develop mould.

- Add mineral fertilizer: Liquid fertilizer could be used to moisten the initial substrate; there is a chance that nutrients are kept in the pores of the lava and so become available for the roots of the developing plant cover. Fertilizer granulate usually comes with the promise of “slow release” of the nutrients which seems advantageous in this case; however, if the plants are not watered regularly, it is questionable whether the granules release any nutrients at all.

- Add microbes: In the special case of nitrogen (see above) certain microbes, unlike plants, have the ability to source from the air. As this process is highly energy demanding, some live in symbiosis with plant roots, other take energy from photosynthesis. Although in research, successes have been made under the key word “Bio-fertilisation practices with plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB)” (e.g. Ruiz 2019), I could not find commercially available products so far.

For the next steps on my journey, I have decided where to go: Existing containers where plants show nutrient deficiency symptoms will be carefully supplemented with a commercial orchid fertilizer. For new containers I will experiment with two selected organic fertilizers as additions to my lava substrate. One is based on pyrolized charcoal and one on earthworm dung. Thanks to the calculations above and based on the NPK declarations on the products, I can easily determine the proper amount of each product to add to my system. As soon as results are available, I will share them here.

5 responses to “Nutrient conditions”

Very interesting article. I can support the experience that pure lava doesn’t hold enough nutrients and that after a year to 1,5 years most plants need a small fertilization.

In the Future I want to add mold resistent oragnic matter directly to the substrate or use it as the top layer of the substrate.

LikeLike

Thank you. Do yo already have an idea of the kind of „mould resistant“ organic material you will be ging to test?

LikeLike

[…] or light. With this in mind, this article begins a three-part series discussing water conditions, nutrient conditions, and light […]

LikeLike

[…] total nitrogen, 1.2% K2O and 0.9% P2O5. With the help of this declaration, I can add exactly the desired amount of nutrients to my container. My product is not sterilized and contains plenty of soil microbes, even tiny […]

LikeLike

[…] supply: As the substrate is not expected to release significant amounts of nutrients in short and medium term, I added liquid fertilizer to the system on two occasions in the total […]

LikeLike