With certain limitations, we consider hermetospheres as closed systems. To get closer to the goal of long-term stability of this system, it is important to understand the conditions and processes within the system. They depend on the initial situation and on external factors such as temperature or light. With this in mind, this article begins a three-part series discussing water conditions, nutrient conditions, and light conditions.

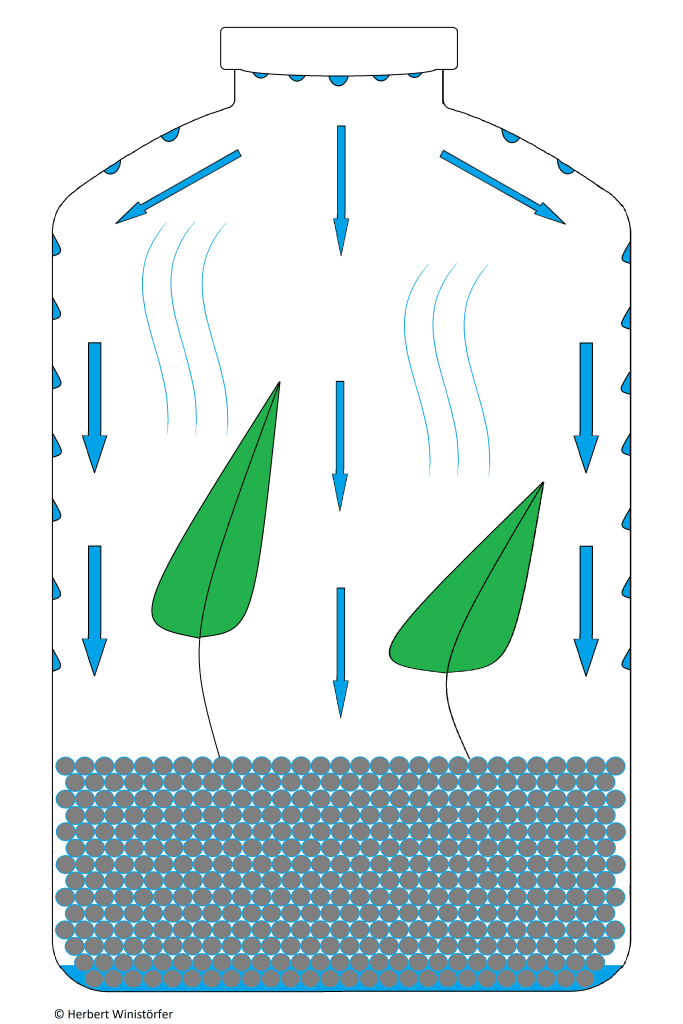

If we follow the advice to start the system with a minimum of stagnant water at the bottom of the container, this will result in an atmosphere above the substrate that is saturated with water vapor. This means the relative humidity of the air is close to 100%. The absolute amount of water in the atmosphere is dependent of the temperature. At higher temperatures, the air contains more water; at lower temperatures some of the water vapor condenses, becomes liquid and gets back into the substrate. Some consequences of the high relative humidity of the atmosphere for plant growth have already been discussed. In this article we will thus focus on the humidity of the substrate, from which most plants obtain their water and nutrients.

The inside of the glass is always slightly warmer than the surroundings. The reason is that glass is transparent to visible light, but not to infrared heat radiation. Light therefore passes through the glass walls of the hermetosphere into the interior, is partially absorbed there by substrate and plants (the darker the material, the more) and is re-emitted as thermal radiation in the far infrared range. As the glass is not permeable to this radiation, it remains inside and heats the air. For this reason, hermetospheres should never be left in direct sunlight for any length of time. This can cause them to heat up so much that the plants are damaged. For the water balance, the temperature difference between inside and outside means that water vapor condenses on the inner walls of the glass and remains visible as drops, trickling down over time. In this way, temperature gradients drive a water cycle of evaporation and condensation inside the glass.

The circulation is further enhanced by temperature differences in the daily rhythm. If the glass is placed on a window sill close to the window glass, which cools down overnight, condensation is also more pronounced on this side of the hermetosphere. On the other hand, if the glass is placed on a shelf against the wall where an artificial light source emits additional heat from above, condensation may not occur at all in the upper part of the glass. This is exactly what I have observed at one of my locations. Two LED strips of 140 cm and 33 W each are placed about 5 cm above the lid of the hermetospheres. The warmth produced by the LED´s is sufficient to prevent any condensation at the top quarter of the glass container.

These details can have consequences for the water conditions in the substrate as well as for the plants. Let me give you two examples:

- Epiphytic bromeliads (e.g., Tillandsioideae) often rely on water uptake by trichomes on the leaf surface, since their roots, if present at all, serve only to anchor the plant (see an earlier post). In a hermetosphere, such a plant is best placed where condensation regularly drips from the lid of the container. Otherwise, the plant may die from dryness even though the substrate is moist.

- Utricularia involvens, a bladderwort loving moist conditions (as most of them do), in competition with moss and ferns only survived at the outermost edge of the substrate where all the condensation water trickles down the surface of the glass (see image below).

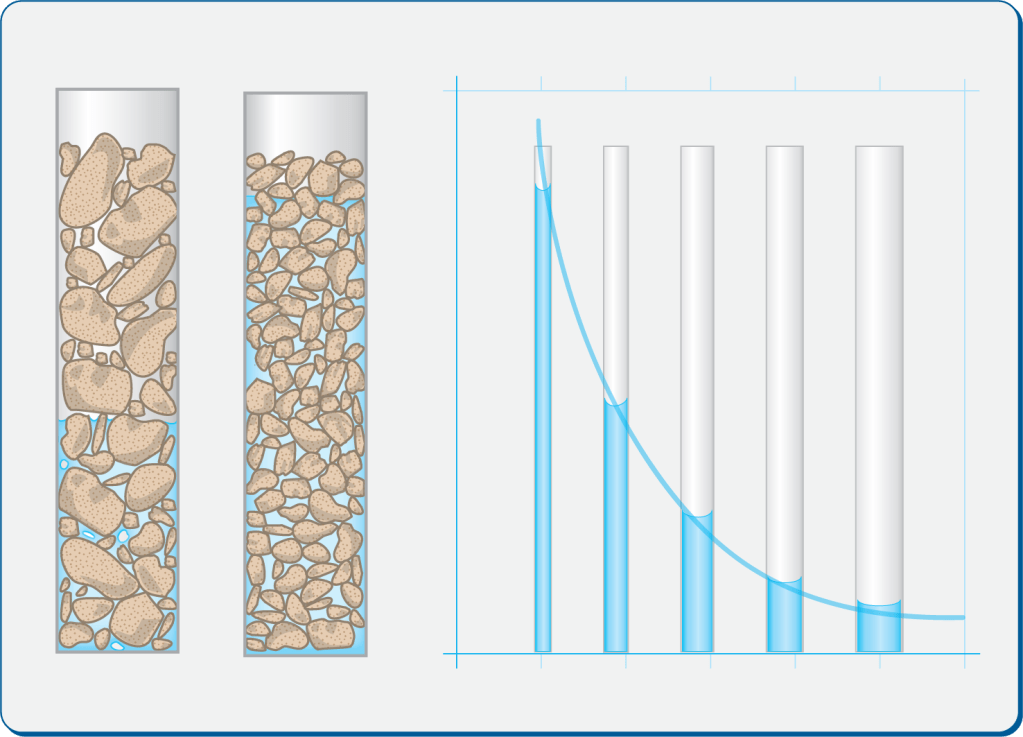

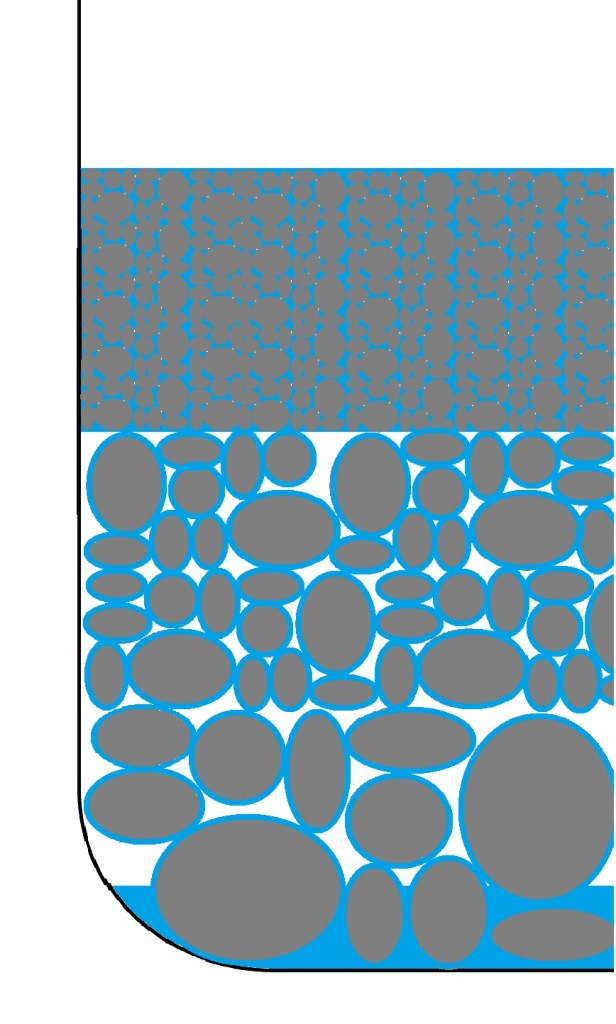

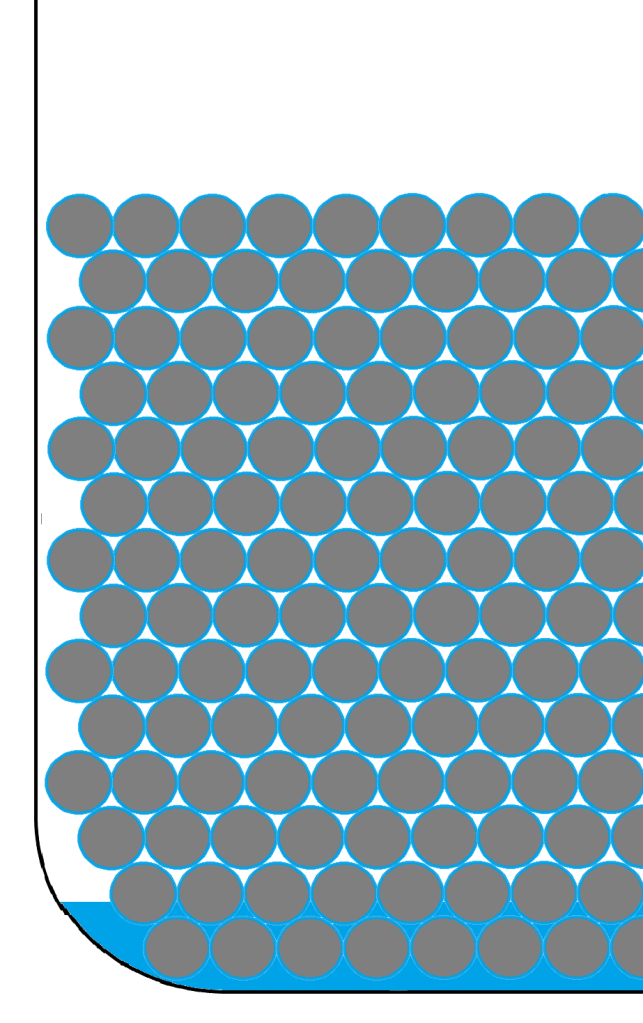

Furthermore, the structure of the substrate affects the water conditions within the hermetosphere. My favorite substrate is simply lava of varying particle size. Lava is a porous material that can retain more water than other mineral substrates. In addition to this, we need to consider capillary effects. Due to these, the lava sand of my choice (0,63-2 mm) retains more water than lava granules with a higher particle size (see illustration below).

In my first attempts, the substrate was always layered with coarse-grained lava at the bottom for good drainage and lava sand on top (see illustration below, a). However, the top layer proved to be too wet for some plants, especially epiphytic/lithophytic miniature orchids. Besides this, it was susceptible to mold growth. As a consequence, I started varying the structure of the substrate according to the soil water or soil air requirements of the intended planting. For plants that need less huimidity and good ventilation of the root zone for example, I choose lava granulate of medium to large (2-8 mm) grain size (see illustration below, b).

As soon as reliable results from these experiments are available, they will be reported here.

2 responses to “Water conditions”

Spannend und so anschaulich illustriert!

LikeLike

[…] In the hermetosphere, it is difficult to mimic the conditions for epiphytes. Here, most of the water condenses on the inner walls of the glass and runs past the plants into the substrate. Terrestrial […]

LikeLike